by C. T. Miéville

I devoured this book in three late-night readings and I couldn’t stop thinking of it during the days in between. It defies generic placement; calling it sci-fi would attach to it a load of unwarranted expectations, yet saying it’s just a noirish crime novel staged in a fictitious setting would hardly do it justice. It’s a captivating, unsettling and above all, incredibly original work of art and imagination.

Before you continue reading, be warned that it will be very hard to avoid spoilers in this review, and that your enjoyment in and appreciation of the book might be entirely ruined if you do get spoiled.

In part, the warning above is naturally tied with the crime-novel aspect of the book, but there’s so much more to it. You might say the setting itself is a mystery, a key accomplice to the crime, and having its nature fully revealed before the finale of the story would dispel the suspense as surely as learning the identity of the criminal. In fact, the mystery of the setting together with the unresolved genre of the book (as meta as that might sound), contribute to the delicious, tantalizing uncertainty even more than the crime itself. It’s this uncertainty – basically the question of whether there is or there is not something truly fantastic about the setting, but also the hunger to learn the whole truth about it, no matter if fantastic or not – that hooked me, with the question of who committed the crime, or why, being only of secondary importance. I’d go as far as to say that the setting is the real mystery, with the crime providing the stage for it, not the other way around. How wonderfully convoluted! Or shall I say, crosshatched.

The story is told from the perspective of the experienced inspector Tyador Borlú, a middle-aged, single man who, true to the noir tradition, we learn almost nothing about during the course of the story. He comes across as quite human nevertheless, due to indirect insights a keen reader can extract from a couple scenes that betray his feelings and motives, and one scene where he succumbs to fear (how embarrassing). These insights are delivered in such a quiet, understated way, that I wondered at times if it was just my own subjective reading. Pretty sure, in the end, that it was deliberate. In any case, it was enough for me to admit him as a proper character and not be disappointed by penetration overly shallow for the first person point of view.

Other characters are unremarkable, with the exception, perhaps, of that of the victim, and to a lesser degree, that of the perpetrator. This shouldn’t be taken as critique, however; simple sketches that they are, Borlú’s side-kicks Corwi, Dhatt and Ashil have their own unique voices and are entirely adequate in their respective roles. Mostly it’s really the same role: that of an interlocutor, someone to ask for and provide with information, someone to compare and contrast with Borlú himself. But they each have one more, distinctive role: that of a representative of their city. This may not be very evident (nor is it necessary) in Corwi, since both she and Borlú are Besz; but it’s quite evident in the impulsive, impatient Dhatt and the secretive, preoccupied Ashil. These qualities are cultural as much as personal, just as their manners, language and clothing.

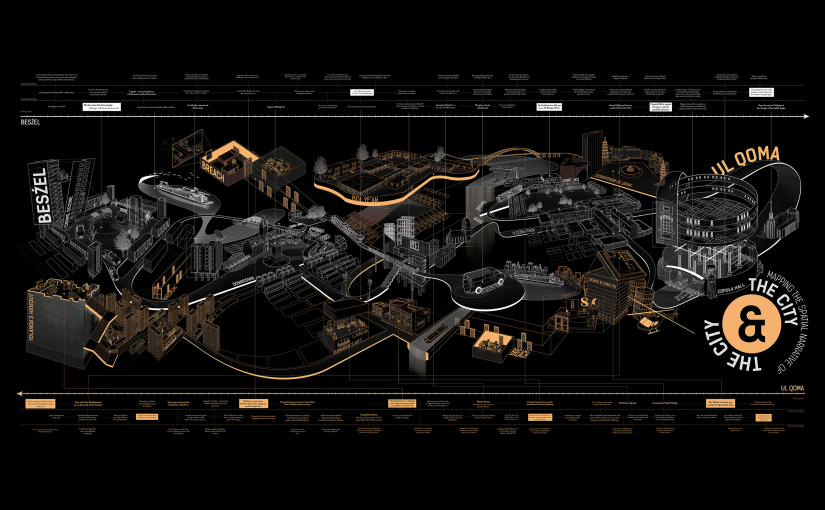

But I’d go one step further and proclaim the cities themselves are characters in this story. Beszel, Ul Quoma and Breach might not have voices or the ability to take direct, personally motivated actions (though this might be disputed in case of Breach), but they are characterized with more care (and more words, for that matter), than any human acting in their stead. Different architectural tendencies, colors, moods, international relations, intricacies of language and behavior are carefully and consistently weaved into every scene and every meditation, until they become equally or even more tangible and familiar than the human cast. In this context, the hidden place, Orciny, plays a role analogous and related to that of both the victim and the criminal, as a thing of mystery, something to remain secret and unexplained even after all the facts of the case are finally laid bare.

The case itself is solid, well thought-out and progresses logically from one stage to the next, with several decently executed turns and tolerably unpredictable resolution. I did see it coming, though not all of it. Wasn’t bothered the least, though, because I was far more invested in the mystery of the setting than that of the crime. I admit I did hope, till the very end, for some evidence of supernatural, and I found the whole deal with the strange archaeological artifacts somewhat lackluster. The one Borlú was threatened with in the end stood out as too vague and arbitrary, with everything else so carefully constructed and described. Overall, though, the plot made enough sense to not ring any alarms and I’m perfectly satisfied with that.

The thing that attracted and unsettled me the most is the concept of unseeing: how it might be witnessed and applied in real life, and how thin the line is between willingly not seeing and being unaware of blindness. How easy it would be to hide in plain sight of people trained to ignore half their reality. One can hardly avoid questioning their own awareness and blindness and susceptibility to exploitation while reading The City and the City. Finding examples of it in everyday experience is painfully easy, what with individuals, whole communities, cultures, buildings and entire neighborhoods one regularly chooses not to notice. Would it really be that hard for a person, or persons, acutely aware of the mechanics of human perception, to walk our cities invisible? While not questions I really take too seriously now, in the light of the day and after finishing the book, they did make me uneasy in those late dark hours while I was deeply immersed in reading. It was a remarkable experience and I’m immensely thankful for both the delightful suspense and the unusual reflections inspired by this wonderful book.

One thought on “The City & The City”